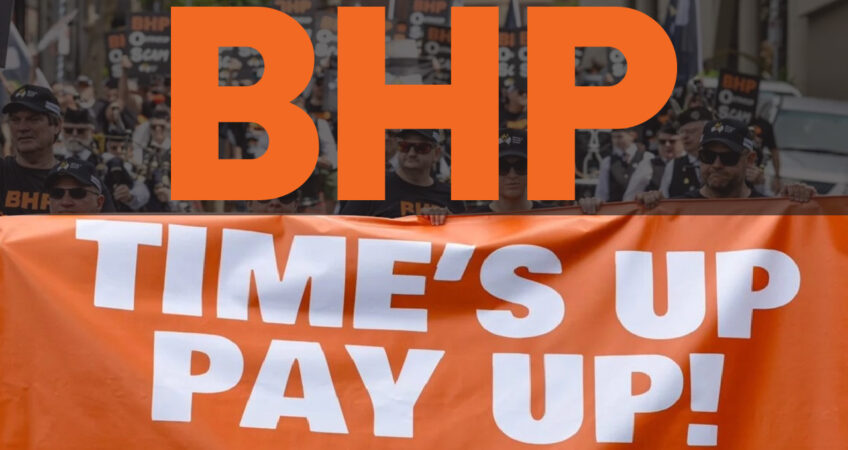

Every week, unions see the consequences of a broken bargaining system. Workers come through our doors with contracts drafted by corporate lawyers, issued en masse by major employers, and signed under pressure—with no room for real negotiation. These are not agreements—they’re ultimatums. The power imbalance couldn’t be clearer. Unless you’re a CEO like Mike Henry (BHP), or represented by one of the many business lobby groups—such as the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Business Council of Australia, Australian Industry Group, or Minerals Council—you’re not getting a real wage increase.

The collapse of genuine collective bargaining at the enterprise level hasn’t delivered a freer or fairer labour market. It has delivered a decade of wage stagnation and growing inequality. With single-employer bargaining effectively dead for most workers, the default has become no bargaining at all.

For over a decade, working people have been told that a real pay rise is just around the corner. We’ve heard it from Treasury officials, Liberal treasurers, Reserve Bank governors, and corporate executives. All talk, no action. In 2015, then-Treasurer Joe Hockey told Australians to “get a good job that pays good money.” In 2021, then-Treasurer Josh Frydenberg claimed a “tighter labour market” would boost wages. Then he encouraged workers to change jobs for better pay. That didn’t work either. Finally, he told us to be patient.

Meanwhile, Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe famously urged workers to “demand higher wages,” while openly acknowledging that employers looked at him like he was “mad” when asked why they didn’t simply offer more pay for in-demand roles. Corporate Australia has made wage suppression a feature of its business model—not a flaw.

And now, in 2025, we’re watching Groundhog Day unfold again. The same employer lobbyists who’ve systematically dismantled collective bargaining since the 1980s are now fearmongering about unions “muscling” their way into the Pilbara and forcing business to collectively bargain. They warn of mass strikes, economic ruin, and collapsing productivity. The Business Council of Australia calls it a “recipe for disaster.” Their message to workers? Don’t rush. Be patient. Stick with the failed system.

Let’s be clear: there is nothing individual about individual contracts—except the pay rate. The terms and conditions are identical, and there is no ability to negotiate. Individual contracts put all the power in the employer’s hands, with a “take it or leave it” attitude. When workers raise concerns about pay and conditions, they’re met with responses like, “the gate swings both ways” or “you should be grateful to have a job.” These remarks reflect the same attitude corporations have held for decades.

The system is broken for most of the workforce, and the result is low pay, insecure work, and entrenched inequality.

We can already hear the business community screeching: “Low pay? Come on, miners are paid well.” On the surface, that argument might convince those who don’t understand the reality of FIFO work. Let’s break it down. An average BHP FIFO salary for a 8:6 roster, working 12-hour shifts, might be $170,000 per year. Sounds high—until you do the math:

$170,000 ÷ 52 weeks ÷ 45 hours per week averaged = $60.54 flat per hour

Is $60.54 per hour really excessive for workers who spend weeks away from their families, working in extreme conditions, and living in often substandard accommodation? It’s not a luxury wage.

Even international institutions are telling us what we already know. The OECD—now led by former Coalition finance minister Mathias Cormann—has endorsed collective bargaining. Their research shows that countries with strong bargaining systems achieve lower wage inequality and better outcomes for workers.

The OECD has called for a revival of collective bargaining to fight wage erosion. Since the inflation crises of the 1970s, most countries have moved away from wage indexation and allowed collective bargaining to decline—giving employers more power to unilaterally set wages and conditions.

It’s no coincidence that the fall in union membership has been followed by falling wages. This was no accident. It was a coordinated effort to demonise unions—led by the business community, enabled by media outlets they influence, and amplified by their political allies in the Liberal and National parties. This led to one of the most effective construction unions; the CFMEU being put into forced administration by the current Labor government. The forced administration was predicated on sensationalised media reporting pushed by the business community and their lobbyists.

And now, we brace for another campaign from big business. Why? Because it’s worked for them before. When the Fair Work Act attempted to revive enterprise bargaining in 2010, the BCA and the Minerals Council claimed it created a “productivity crisis.” Never mind that productivity was actually increasing. Their fear campaign led to a review that ultimately recommended cutting penalty rates for hospitality and retail workers. Those pay cuts were delivered—while profits soared.

Now, the same businesses and their lobby groups that helped destroy enterprise bargaining are saying that the sky is going to fall in and that it is best placed to drive wage growth by directly dealing with its employees. It’s shameless—and workers aren’t buying it.

Unions know the truth: without strong collective bargaining rights, workers have no real power. Collective bargaining is not a radical idea. It’s a fundamental tool for fairness, but one that’s been buried under decades of misinformation. Workers have been told they’re better off negotiating as individuals—when in reality, individuals have no real leverage against multinational corporations.

So, the next time business lobbyists knock on the doors of Parliament House, trying to delay reform or dismantle worker protections in the Fair Work Act, politicians should ask just one question:

When are you going to start sharing record profits with the people who create them?